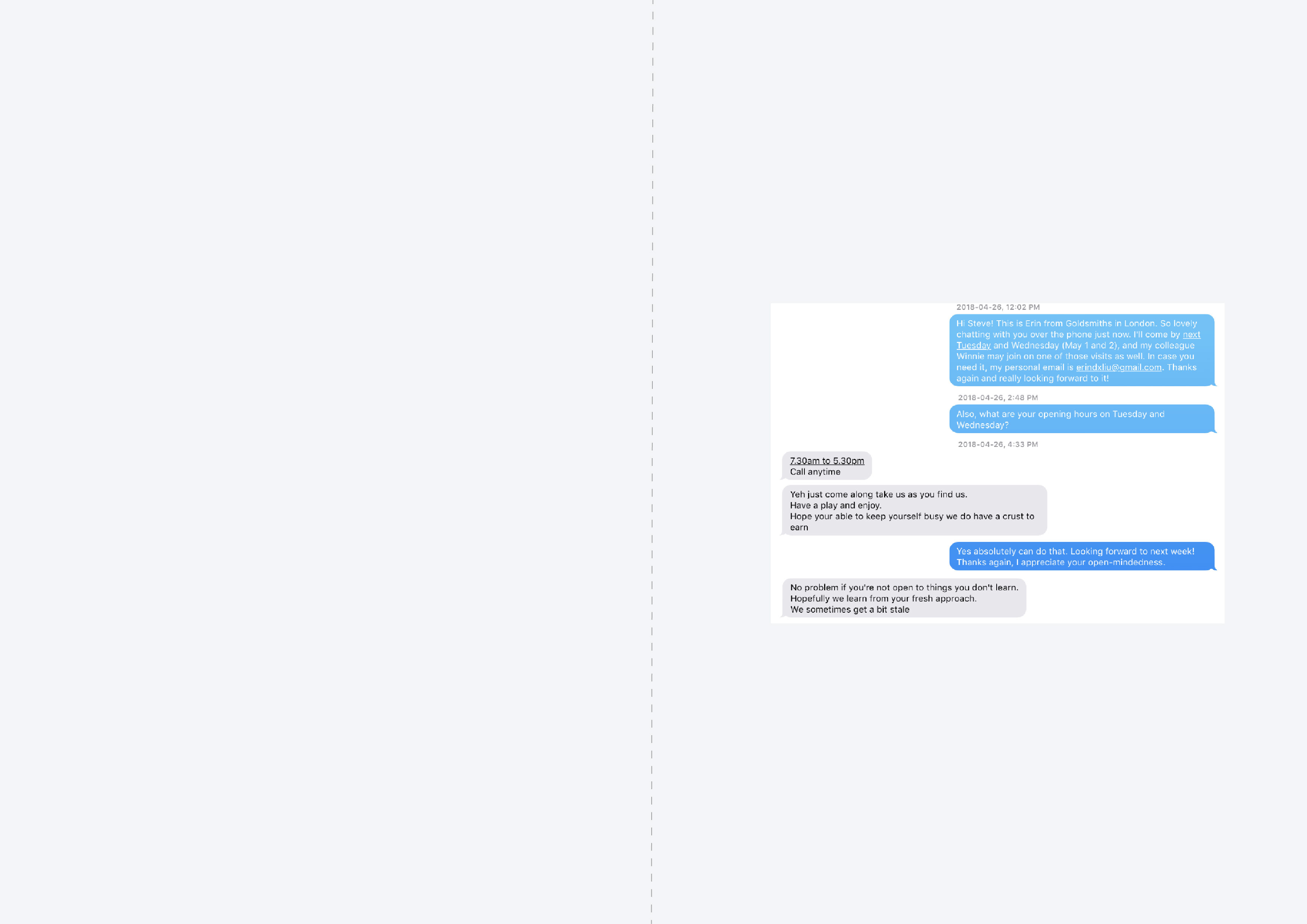

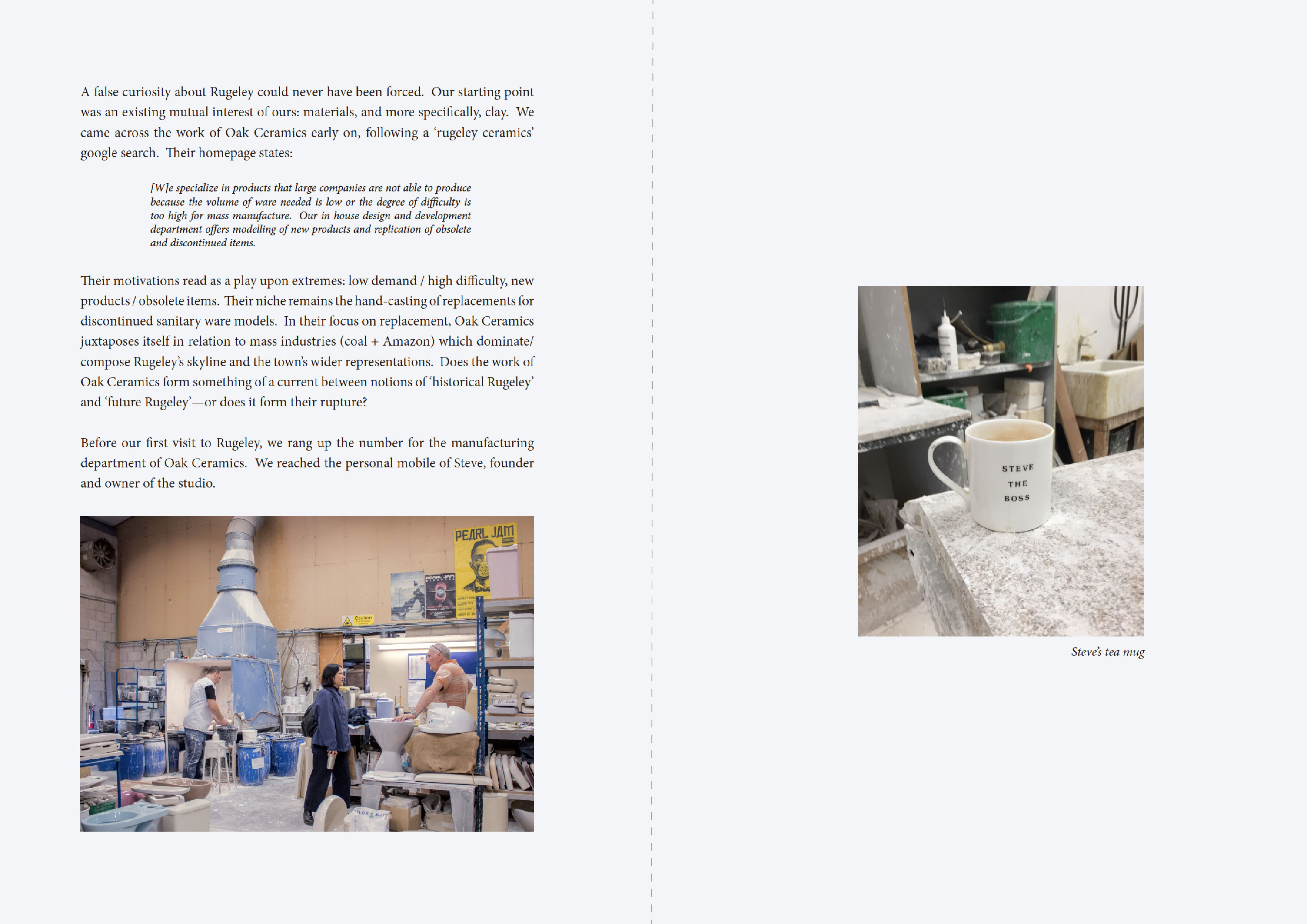

My colleague Erin and I shadowed the folks at Oak Ceramics in a town called Rugeley in the East Midlands. Their niche remains the hand-casting of replacements for discontinued sanitary ware models, where there knowledge in this area is 'second-to-none.' In their focus on replacement, Oak Ceramics juxtaposes itself in relation to mass industries (coal + Amazon) which dominate/ compose Rugeley’s skyline and the town’s wider representations.

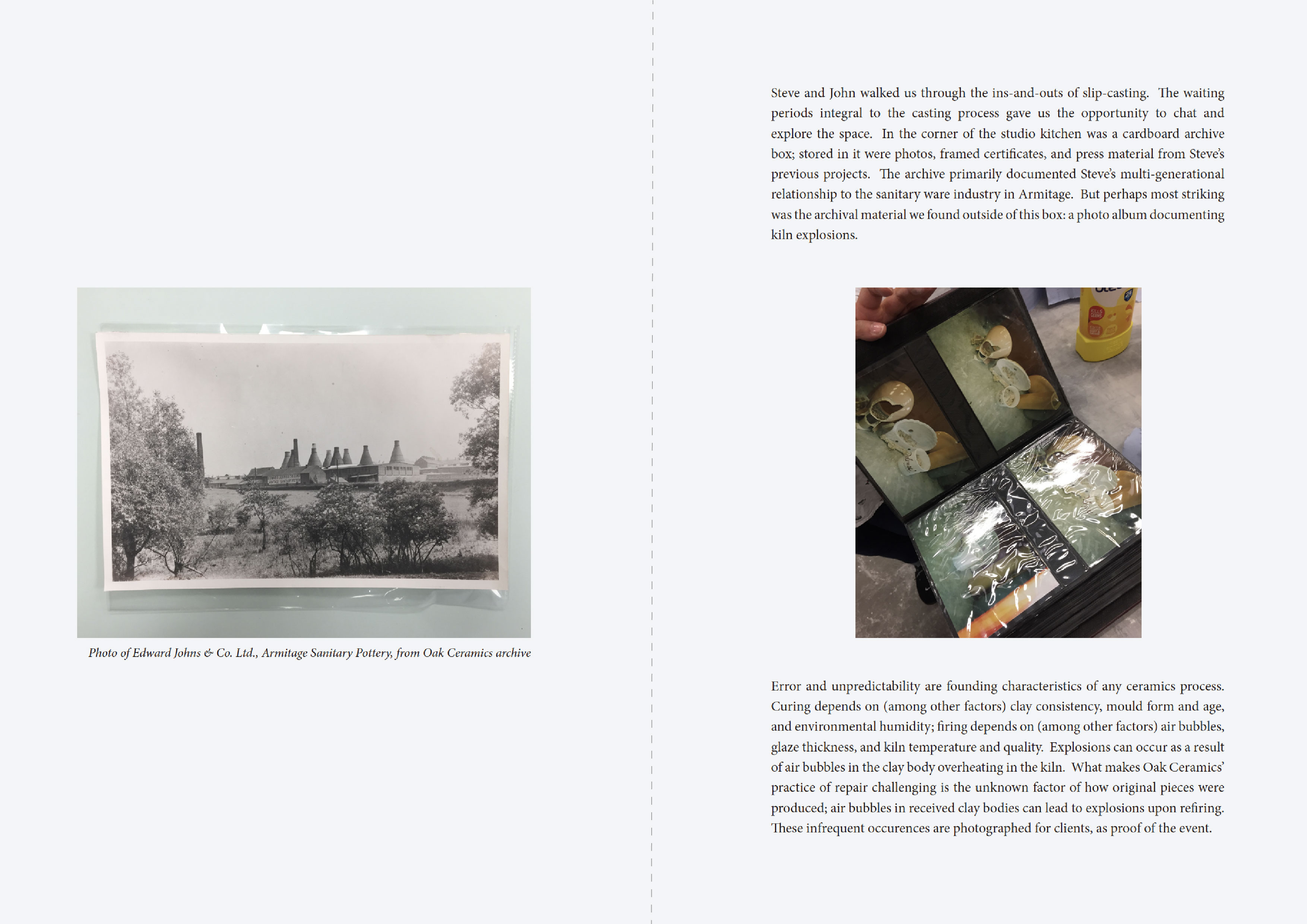

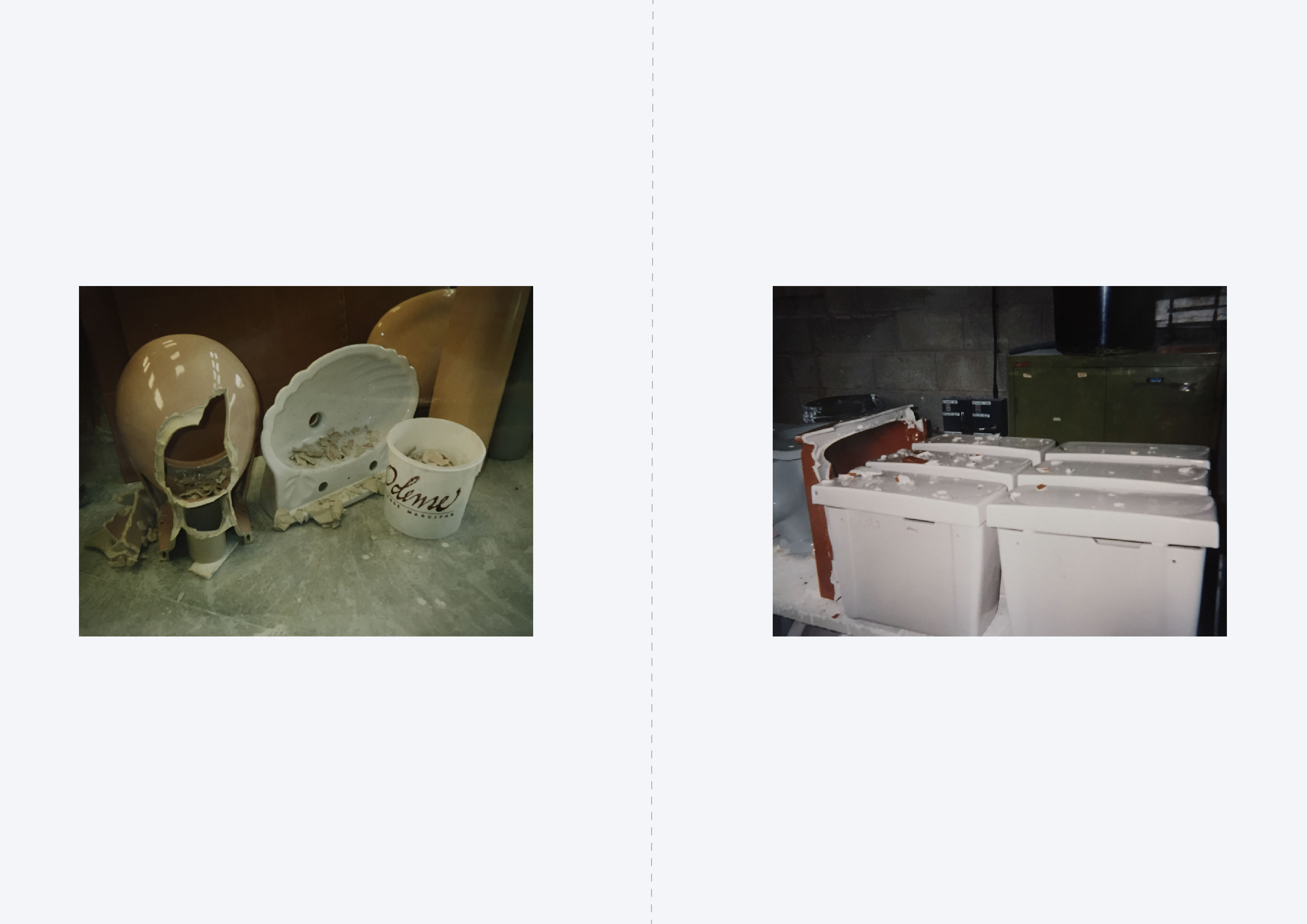

Error and unpredictability are founding characteristics of any ceramics process. Curing depends on (among other factors) clay consistency, mould form and age, and environmental humidity; firing depends on (among other factors) air bubbles, glaze thickness, and kiln temperature and quality. Explosions can occur as a result of air bubbles in the clay body overheating in the kiln.

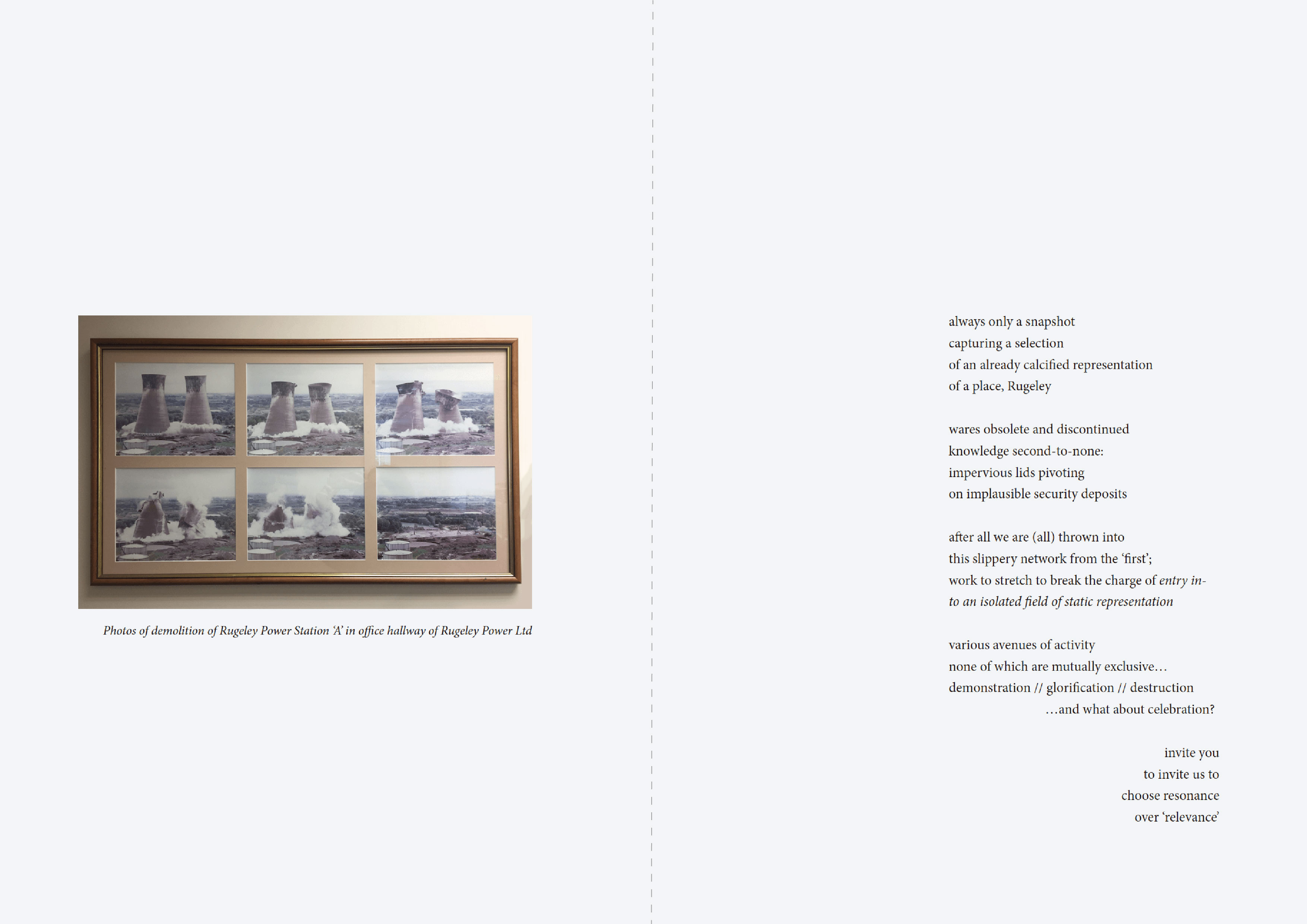

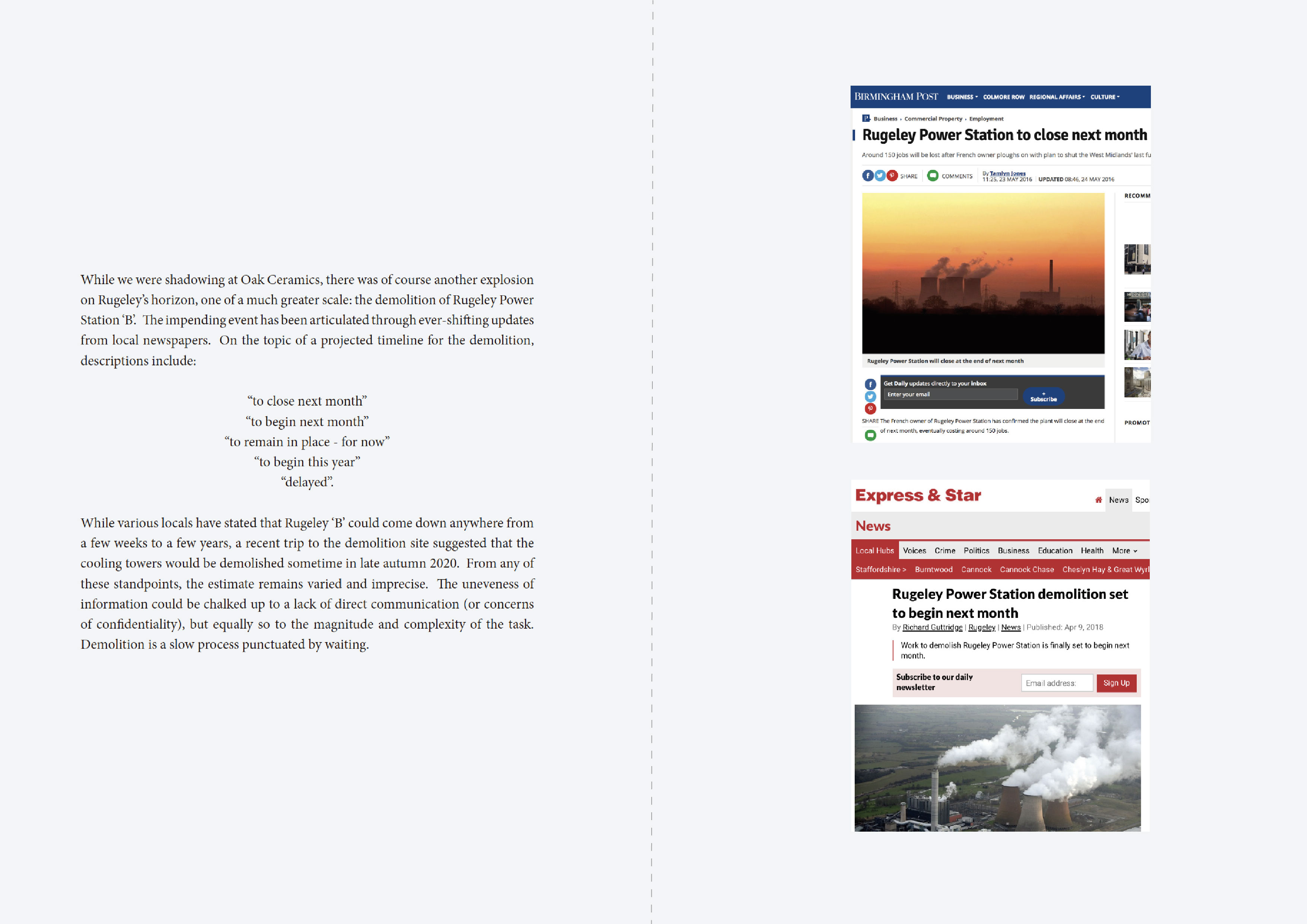

While we were learning at Oak Ceramics, there was of course another explosion on Rugeley’s horizon, one of a much greater scale: the demolition of Rugeley Power Station ‘B’. The impending event has been articulated through ever-shifting updates from local newspapers.

Error and unpredictability are founding characteristics of any ceramics process. Curing depends on (among other factors) clay consistency, mould form and age, and environmental humidity; firing depends on (among other factors) air bubbles, glaze thickness, and kiln temperature and quality. Explosions can occur as a result of air bubbles in the clay body overheating in the kiln.

While we were learning at Oak Ceramics, there was of course another explosion on Rugeley’s horizon, one of a much greater scale: the demolition of Rugeley Power Station ‘B’. The impending event has been articulated through ever-shifting updates from local newspapers.

On the topic of a projected timeline for the demolition, descriptions include:

“to close next month”

“to begin next month”

“to remain in place - for now”

“to begin this year”

“delayed”.

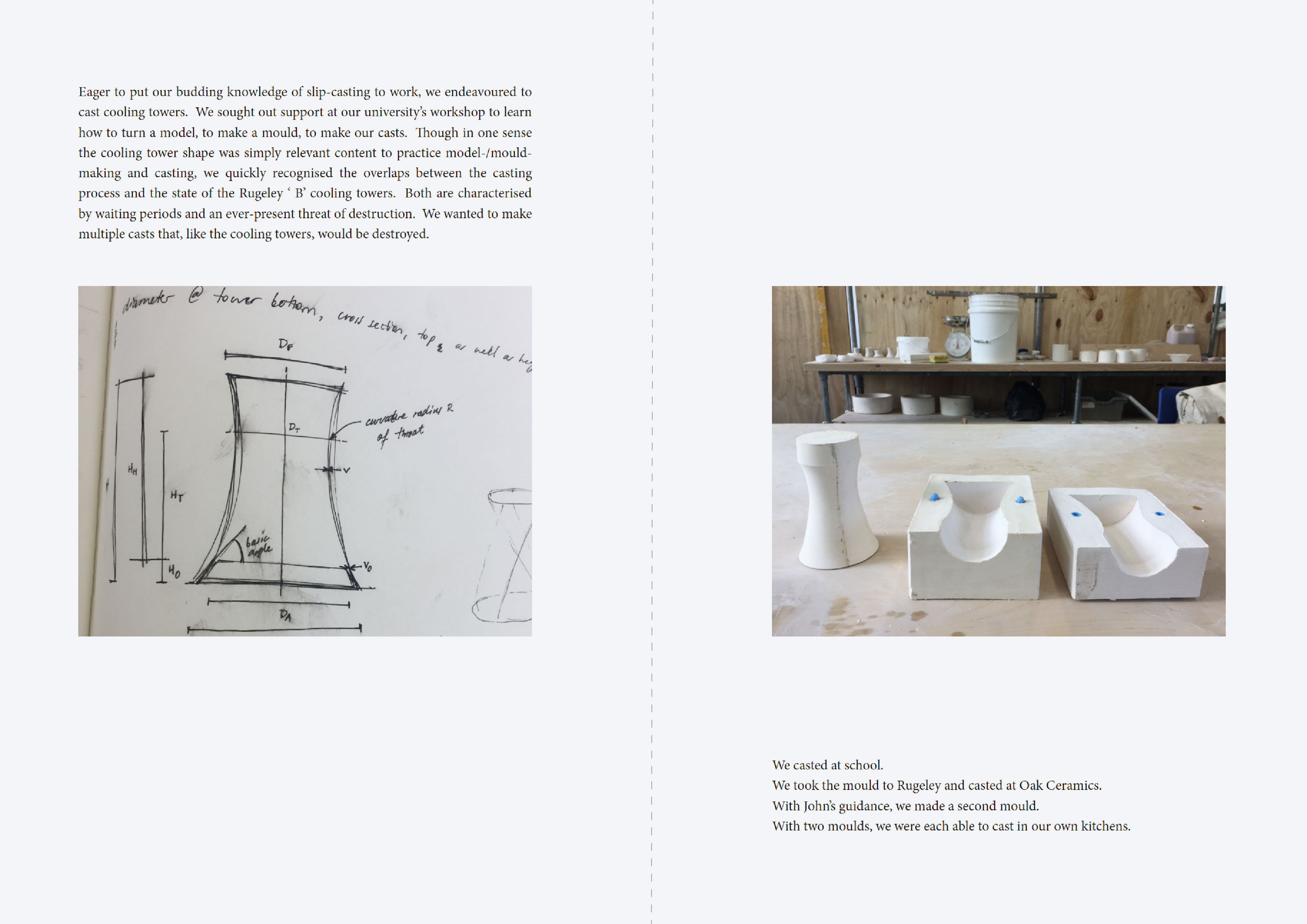

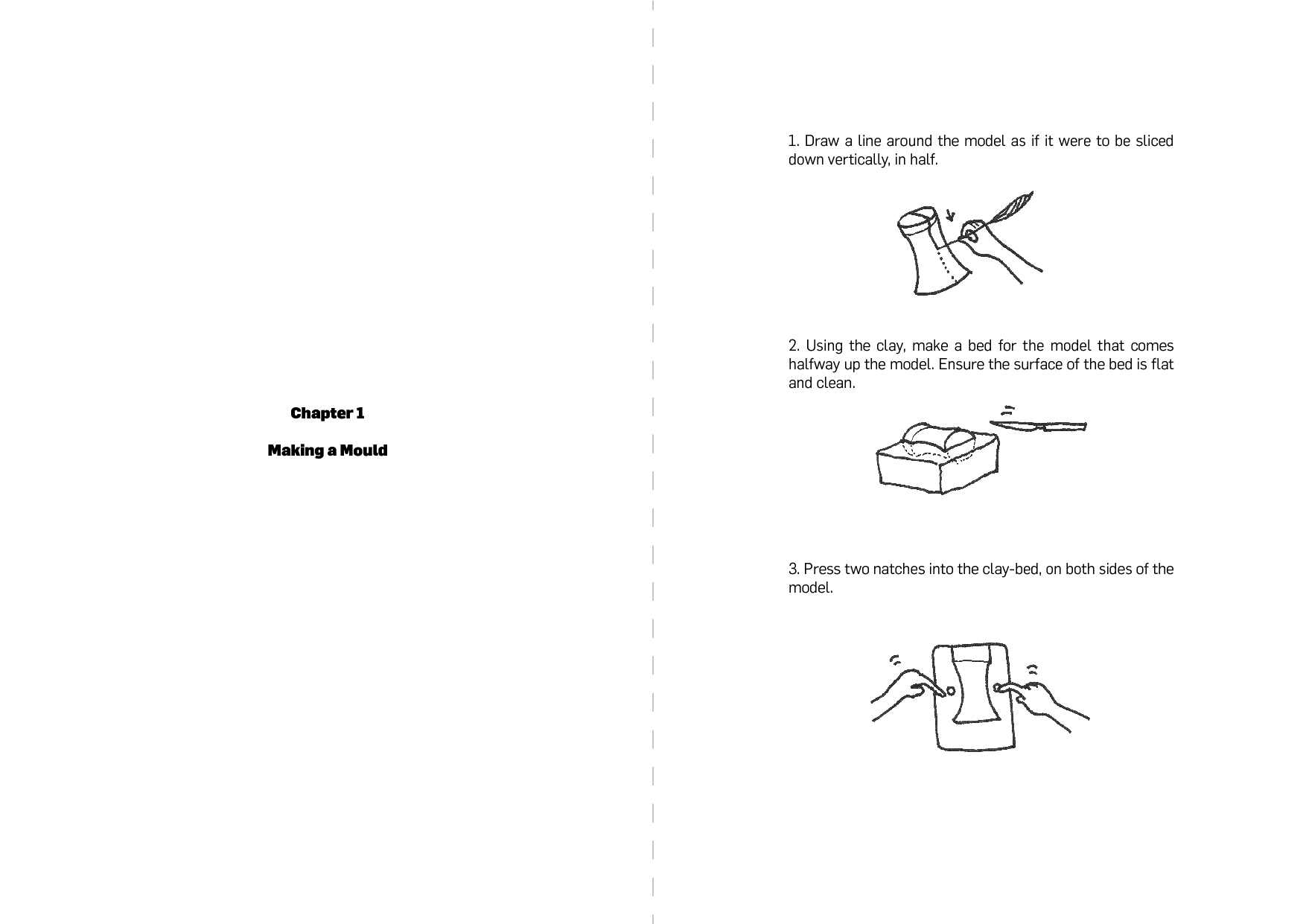

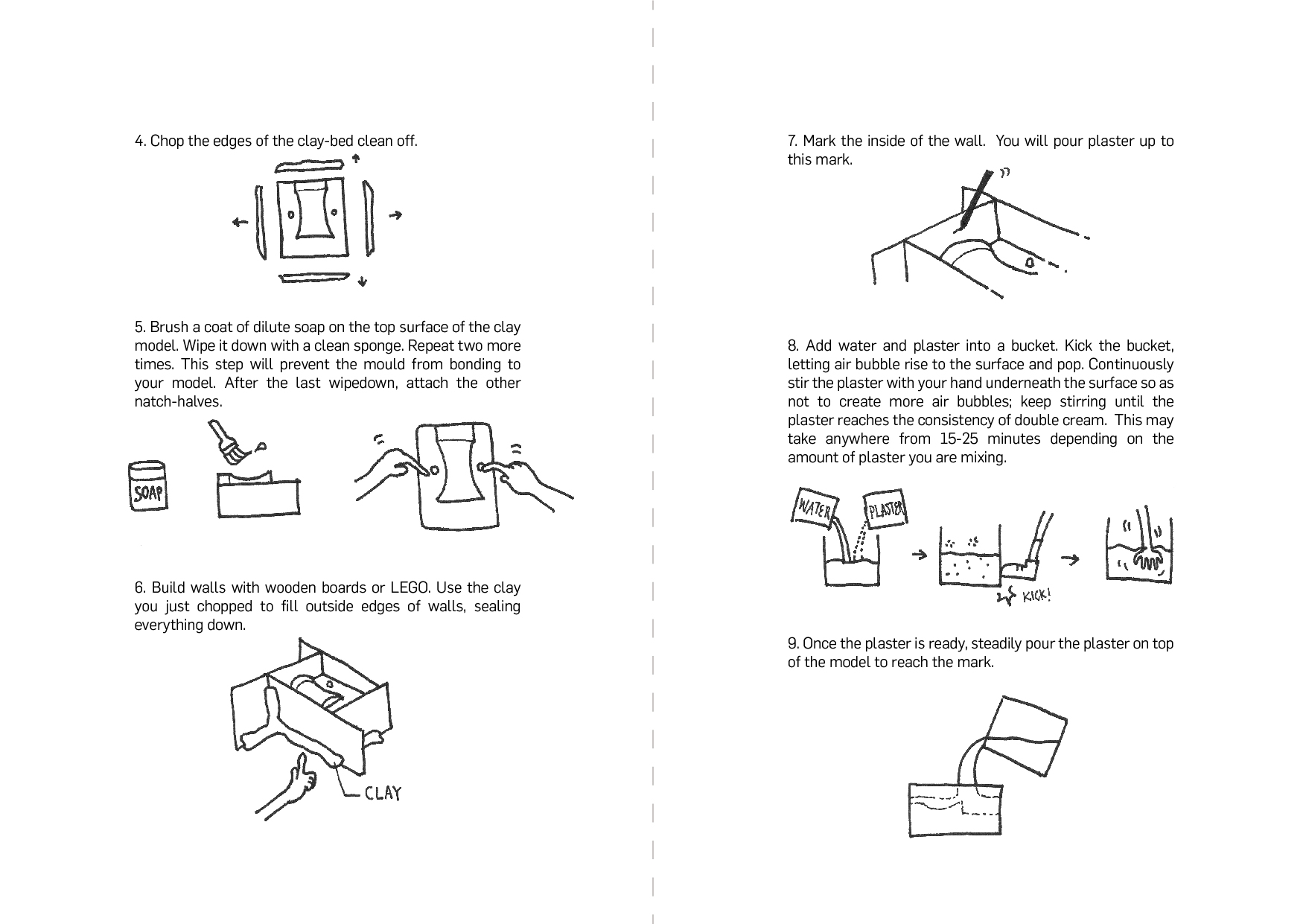

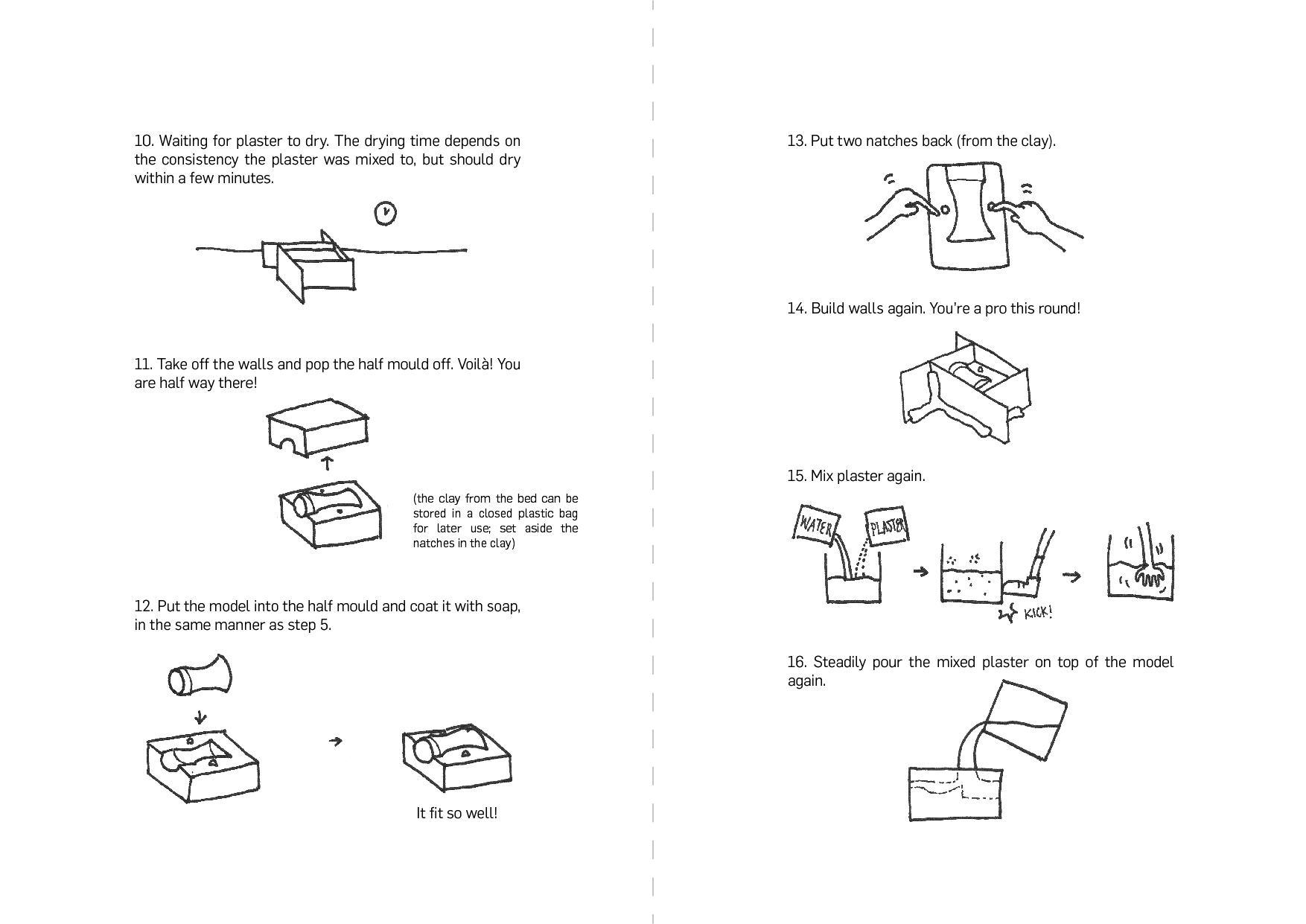

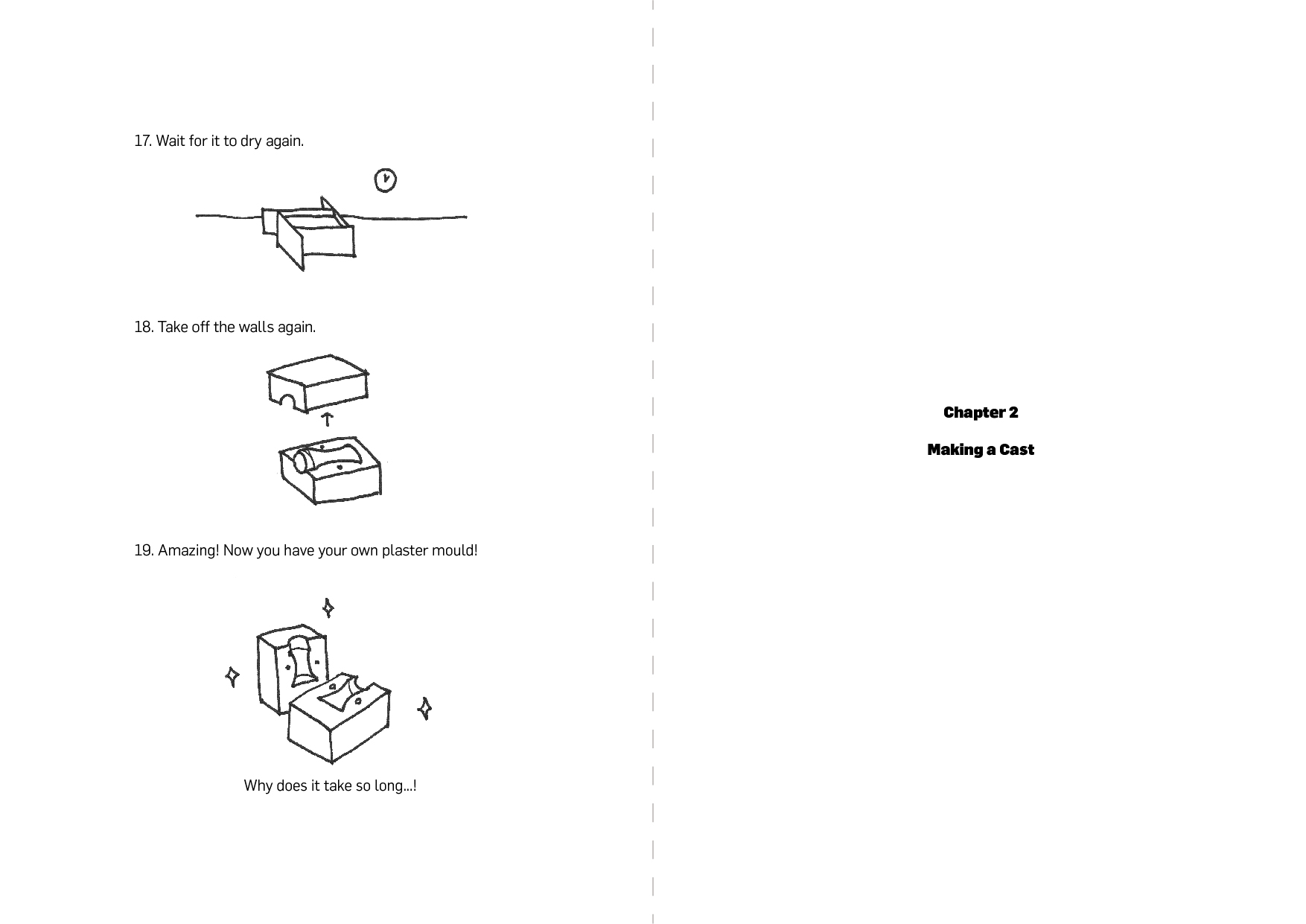

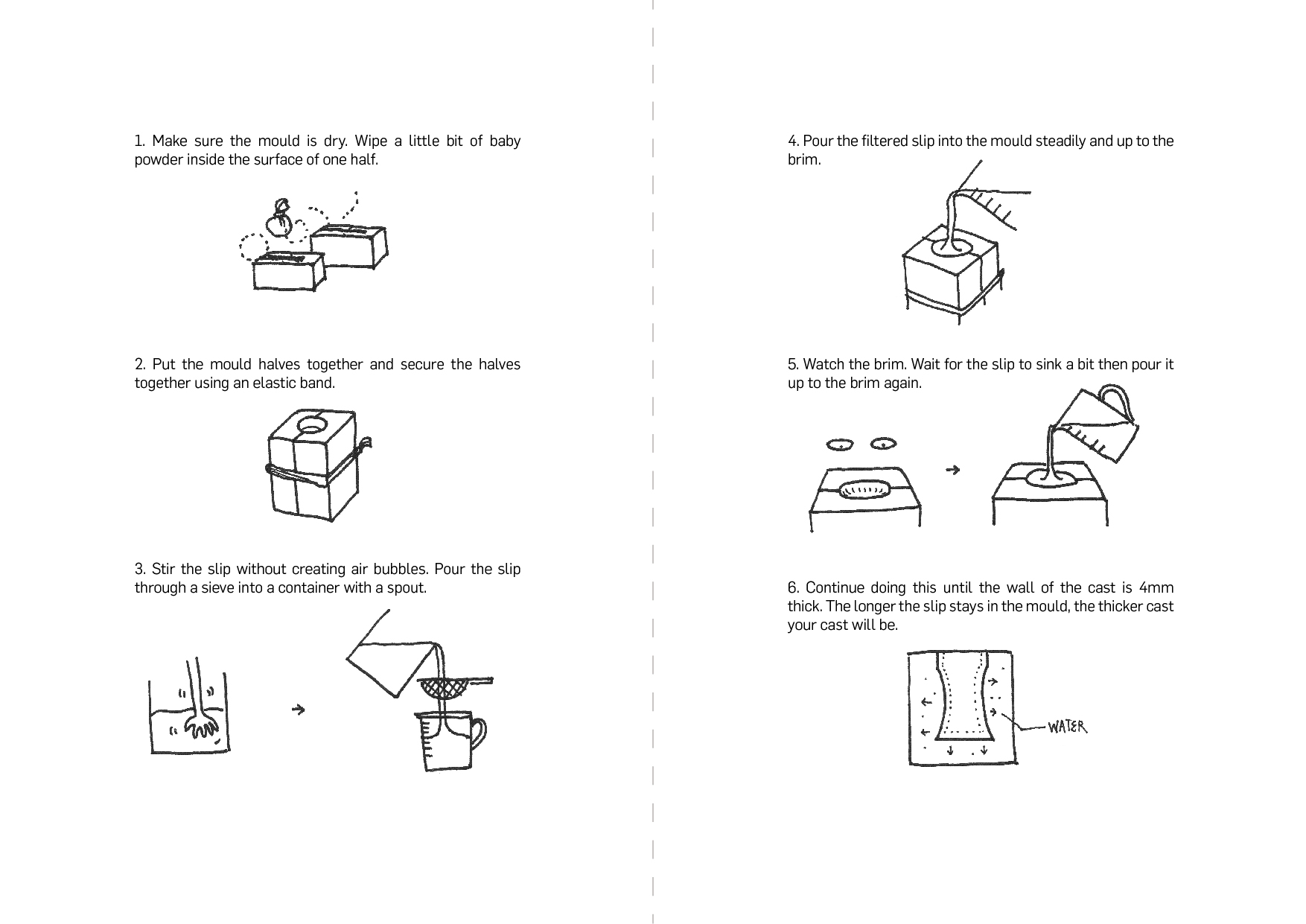

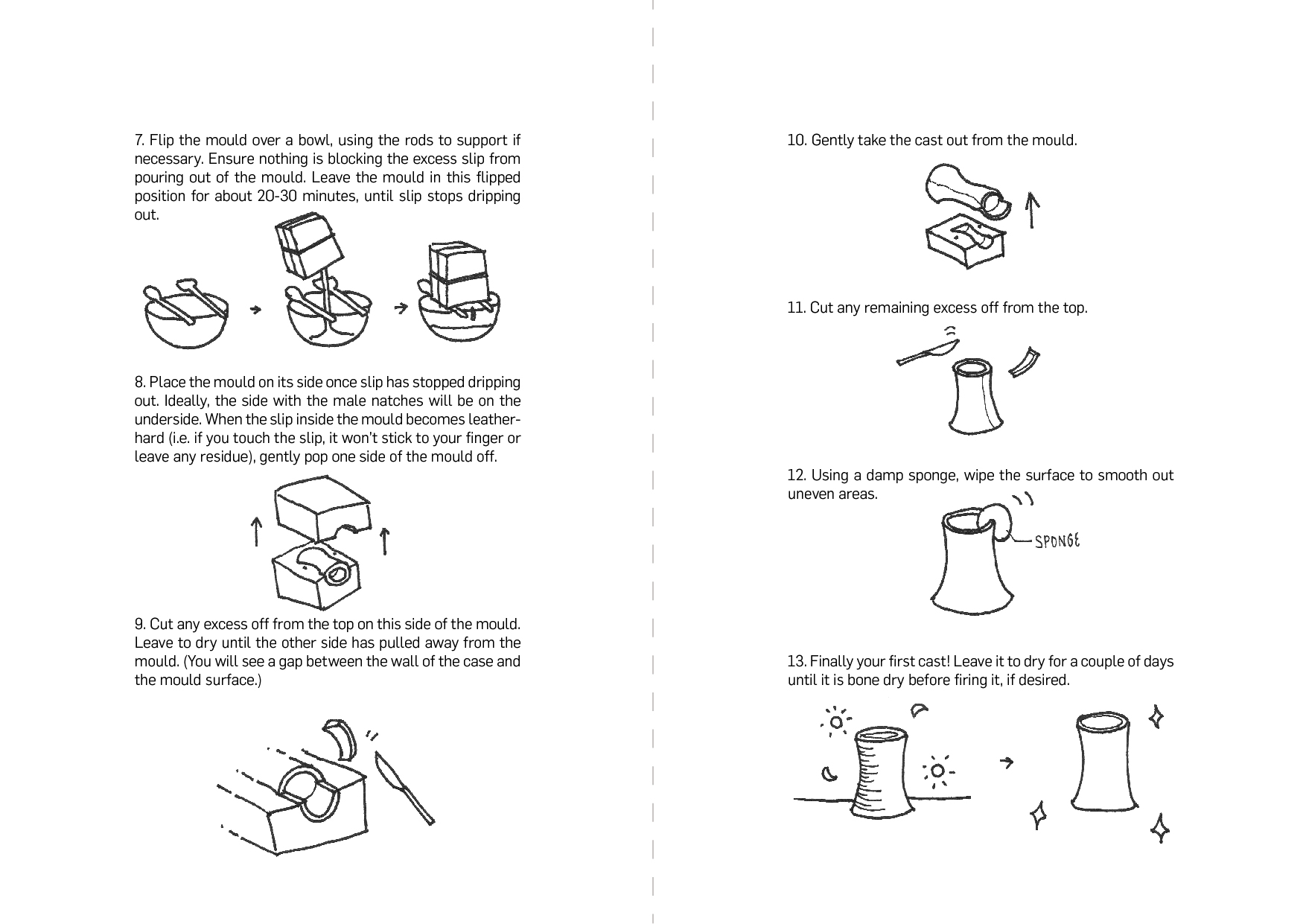

Eager to put our budding knowledge of slip-casting to work, we endeavoured to cast cooling towers. We sought out support at our university’s workshop to learn how to turn a model, to make a mould, to make our casts. Though in one sense the cooling tower shape was simply relevant content to practice model-/mould-making and casting, we quickly recognised the overlaps between the casting process and the state of the Rugeley ‘ B’ cooling towers. Both are characterised by waiting periods and an ever-present threat of destruction. We wanted to make multiple casts that, like the cooling towers, would be destroyed.

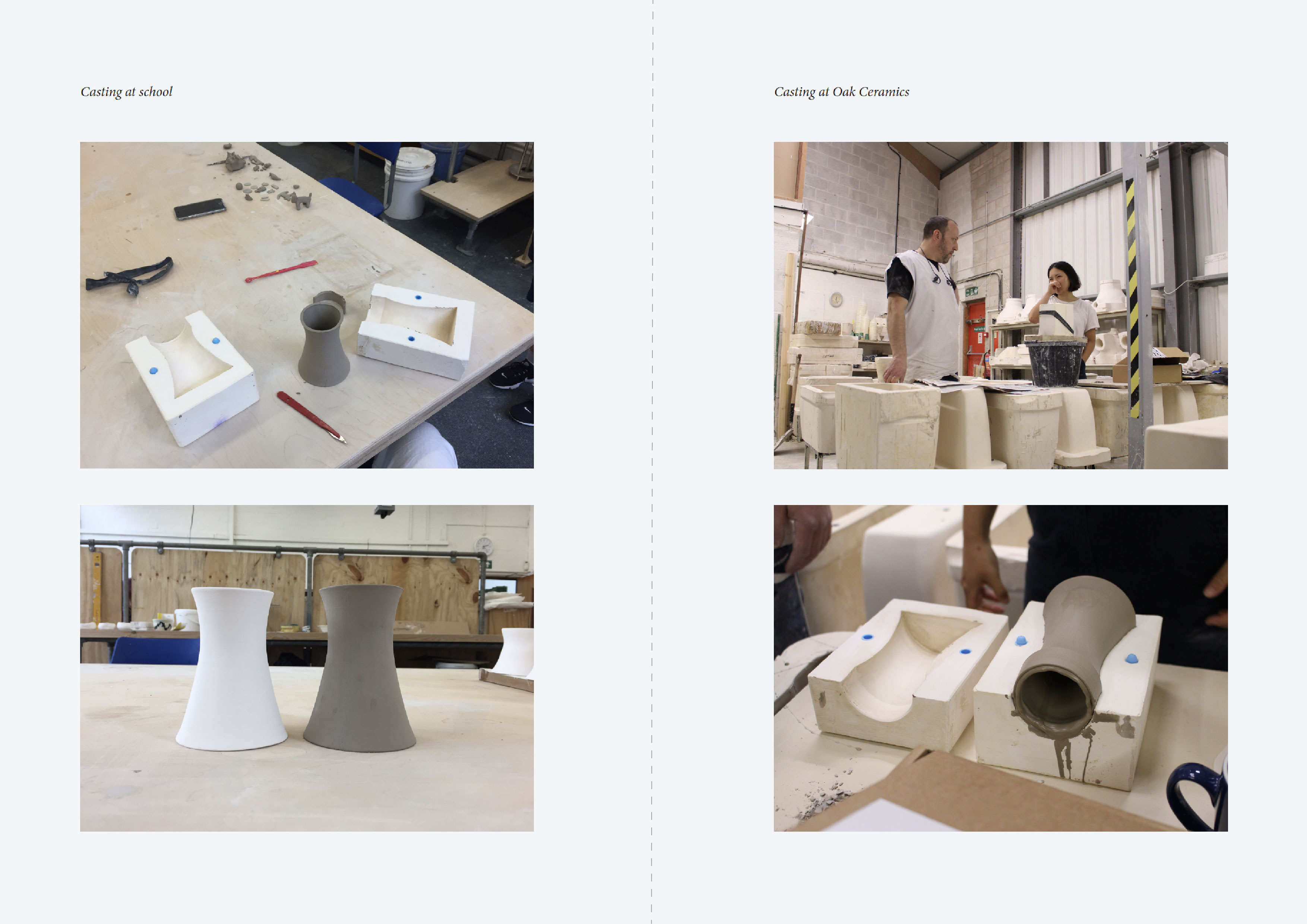

We casted at school. We took the mould to Rugeley and casted at Oak Ceramics. With John’s guidance, we made a second mould. With two moulds, Molly and I were each able to cast in our own kitchens.

“to close next month”

“to begin next month”

“to remain in place - for now”

“to begin this year”

“delayed”.

Eager to put our budding knowledge of slip-casting to work, we endeavoured to cast cooling towers. We sought out support at our university’s workshop to learn how to turn a model, to make a mould, to make our casts. Though in one sense the cooling tower shape was simply relevant content to practice model-/mould-making and casting, we quickly recognised the overlaps between the casting process and the state of the Rugeley ‘ B’ cooling towers. Both are characterised by waiting periods and an ever-present threat of destruction. We wanted to make multiple casts that, like the cooling towers, would be destroyed.

We casted at school. We took the mould to Rugeley and casted at Oak Ceramics. With John’s guidance, we made a second mould. With two moulds, Molly and I were each able to cast in our own kitchens.

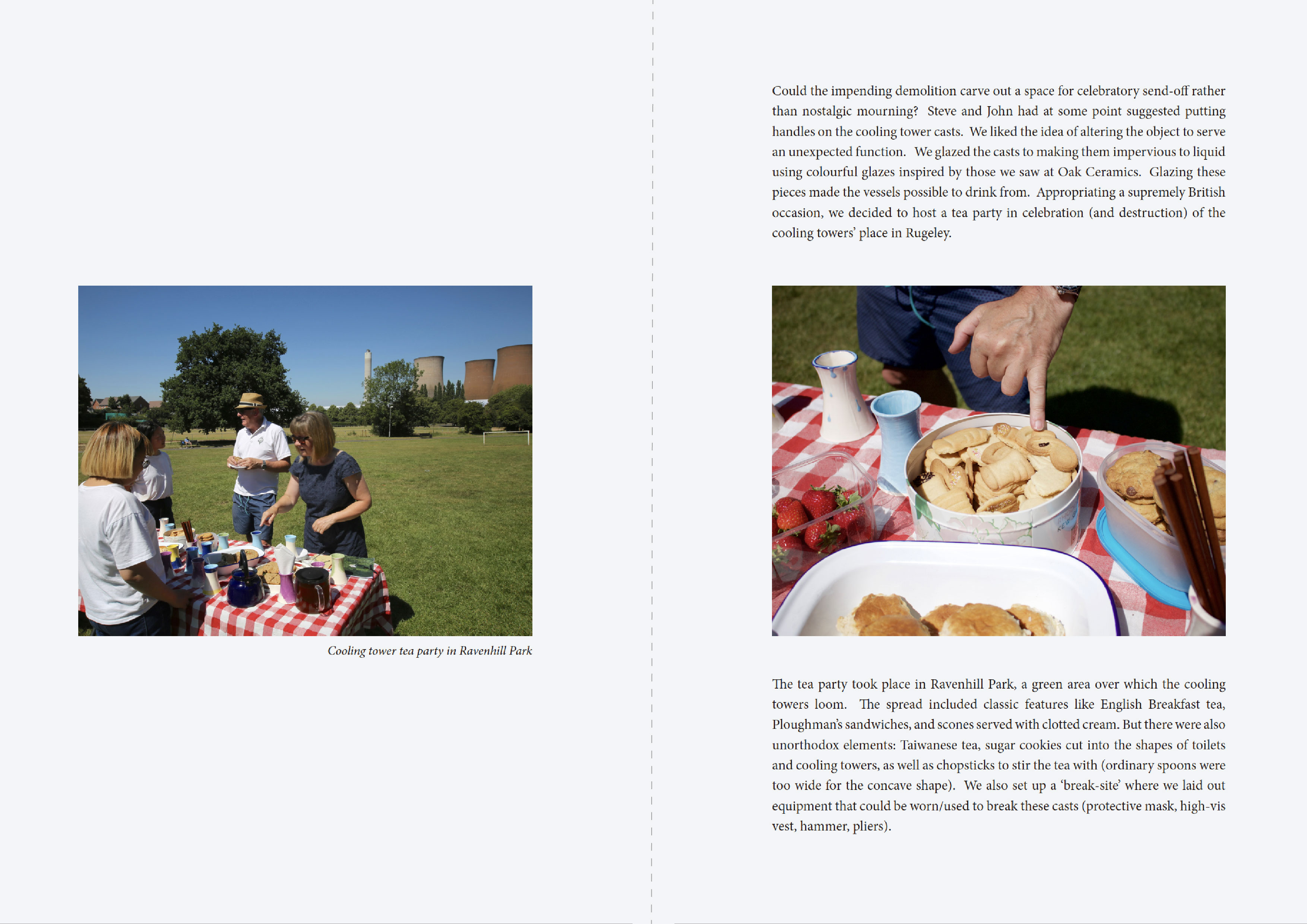

Could the impending demolition carve out a space for celebratory send-off rather than nostalgic mourning? Steve and John from Oak Ceramics had at some point suggested putting handles on the cooling tower casts. We liked the idea of altering the object to serve an unexpected function. We glazed the casts to making them impervious to liquid using colourful glazes inspired by those we saw at Oak Ceramics. Glazing these pieces made the vessels possible to drink from. Appropriating a supremely British occasion, we decided to host a tea party in celebration (and destruction) of the cooling towers’ place in Rugeley.

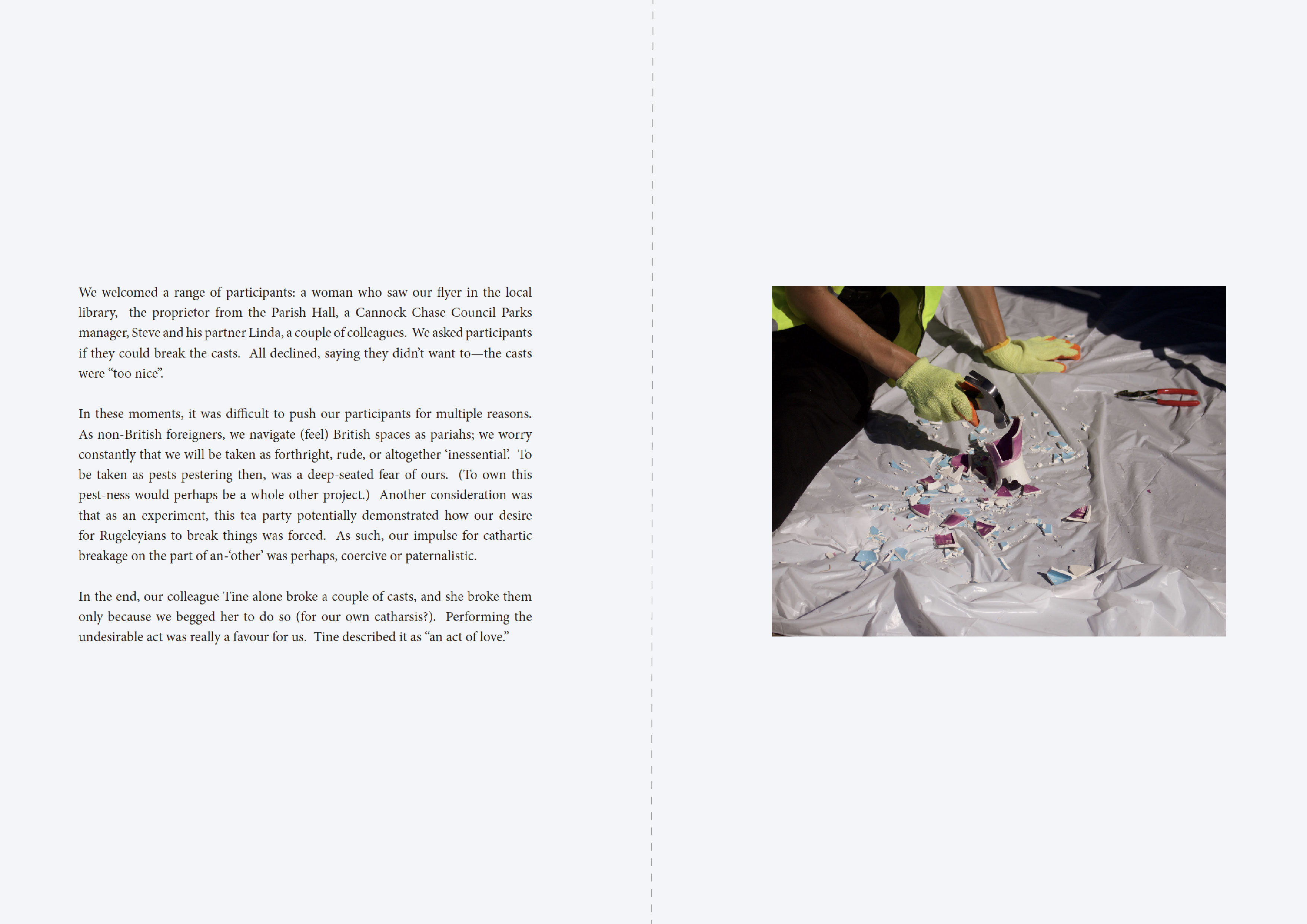

The tea party took place in Ravenhill Park, a green area over which the cooling towers loom. The spread included classic features like English Breakfast tea, Ploughman’s sandwiches, and scones served with clotted cream. But there were also unorthodox elements: Taiwanese tea, sugar cookies cut into the shapes of toilets and cooling towers, as well as chopsticks to stir the tea with (ordinary spoons were too wide for the concave shape). We also set up a ‘break-site’ where we laid out equipment that could be worn/used to break these casts (protective mask, high-vis vest, hammer, pliers).

The tea party took place in Ravenhill Park, a green area over which the cooling towers loom. The spread included classic features like English Breakfast tea, Ploughman’s sandwiches, and scones served with clotted cream. But there were also unorthodox elements: Taiwanese tea, sugar cookies cut into the shapes of toilets and cooling towers, as well as chopsticks to stir the tea with (ordinary spoons were too wide for the concave shape). We also set up a ‘break-site’ where we laid out equipment that could be worn/used to break these casts (protective mask, high-vis vest, hammer, pliers).

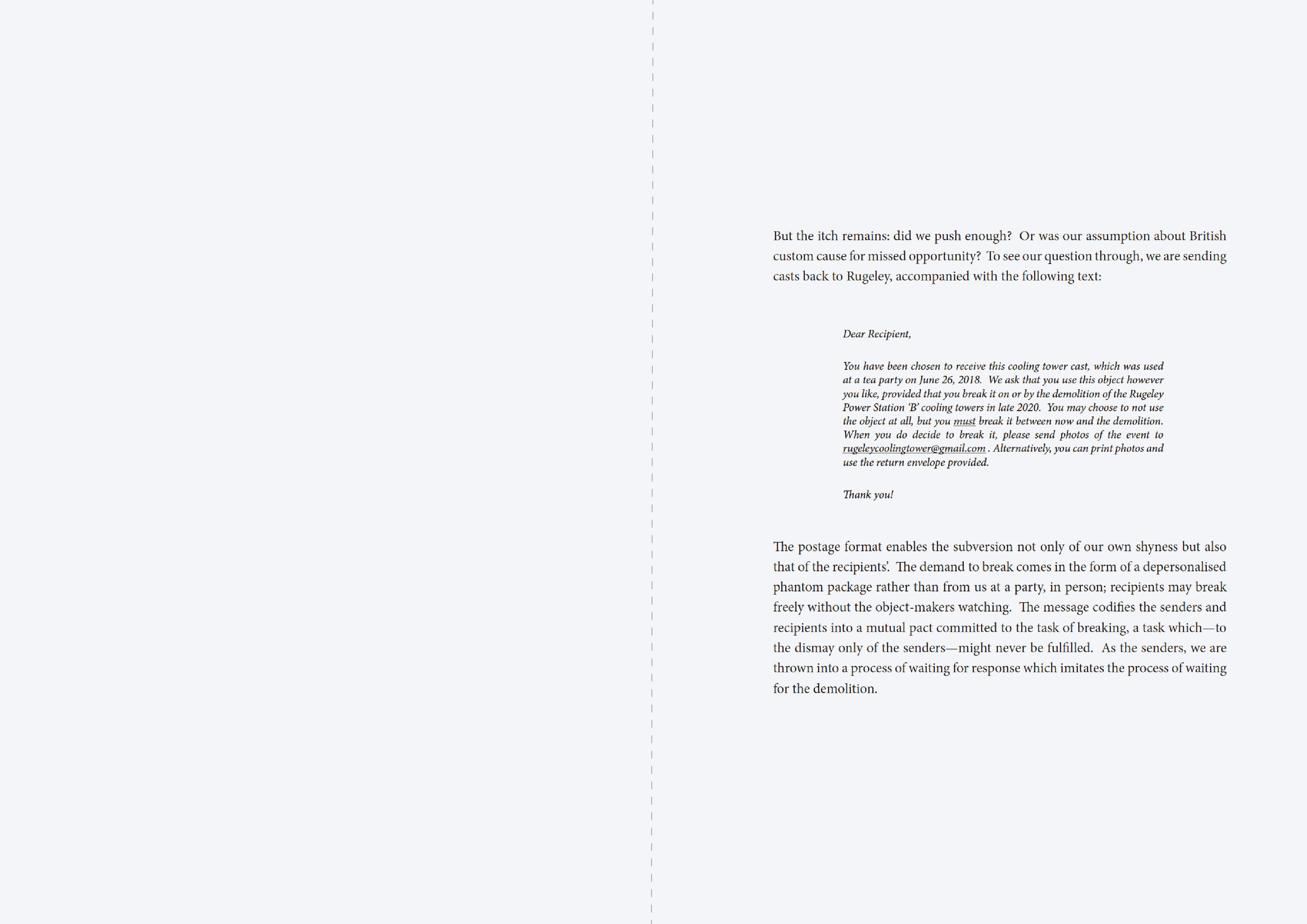

We asked participants if they could break the casts. All declined, saying they didn’t want to—the casts were “too nice”. In these moments, it was difficult to push our participants for multiple reasons. As non-British foreigners, we navigate (feel) British spaces as pariahs; we worry constantly that we will be taken as forthright, rude, or altogether ‘inessential’. To be taken as pests pestering then, was a deep-seated fear of ours. (To own this pest-ness would perhaps be a whole other project.) Another consideration was that as an experiment, this tea party potentially demonstrated how our desire for Rugeleyians to break things was forced. As such, our impulse for cathartic breakage on the part of an-‘other’ was perhaps, coercive or paternalistic.

In the end, our colleague Tine alone broke a couple of casts, and she broke them only because we begged her to do so (for our own catharsis?). Performing the undesirable act was really a favour for us. Tine described it as “an act of love.”

In the end, our colleague Tine alone broke a couple of casts, and she broke them only because we begged her to do so (for our own catharsis?). Performing the undesirable act was really a favour for us. Tine described it as “an act of love.”

Zine

Process Book